Exploring a subscription model for corporate action on biodiversity (and whether durability is a necessary criteria for nature credits)

Building on the discussions of whether nature credits are commodities or assets, let's take a look a subscription model and whether durability makes sense in the nature credit context

Simas Gradeckas’ recent article brilliantly highlighted the upsides and downsides of whether we treat biodiversity like a commodity (coffee) or like an asset (land). It got my gears going on a potential third option for nature credits, the subscription model.

A subscription model may incorporate flavors of both and I think is worth considering as we look at the different ways that we can best develop the structure/mechanism to compensate for the value of nature most effectively, equitably and sustainably.

One-off payment vs Subscription

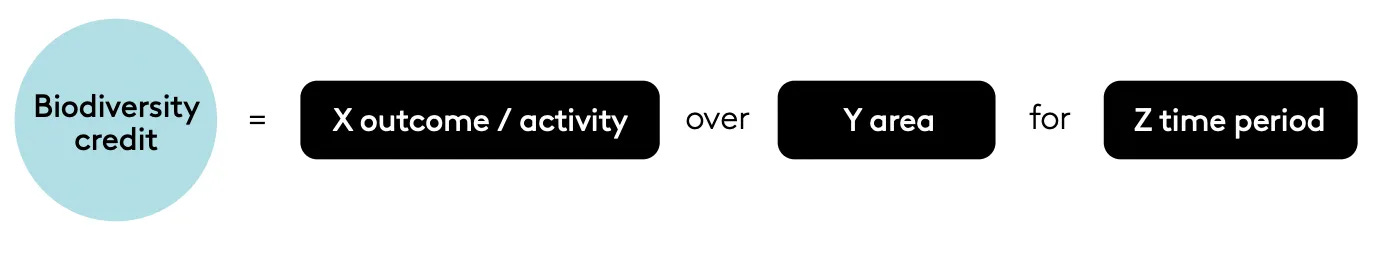

Pulling from Simas’ article which originally came from Pollination, a biodiversity (or other ecosystem service) credit within a commodity structure represents an outcome or activity within a specific area over a defined period of time.

Figure 5: Pollination: State of Voluntary Biodiversity Credit Market

A subscription, if I’m thinking about it correctly, might be somewhat of a step towards an asset (long-term investment) from a commodity (one-off payment). A commodity (credit) that represents a nature positive outcome could be sold via a subscription model such that the same buyer would be purchasing an continually delivered outcome from the same area over a period of time.

This is a step towards the asset approach in that it incentivizes longer-term commitment to a particular area/region, but without the buyer being able to participate in the value of the underlying asset itself (often the land). Which may or may not be beneficial depending on whose perspective you take.

From the corporate perspective, they might prefer a subscription approach because it allows for them to commit to longer term support of nature positive outcomes in a particular region without taking an investment risk in an underlying asset. But on the other side of the coin, they may want to own or directly invest in the asset in order to potentially have a financial gain from the area where they are purchasing credits or subscribing.

From the perspective of an indigenous land steward, they may want to sell a “subscription” to someone to purchase and claim the nature positive outcomes from the region they are stewarding without the complications of groups investing in the underlying asset, especially where indigenous cultural law does not include property ownership. For this to work, especially in the case where there is no land rights for the indigenous group or local community/land stewards, we may need to develop a new legal designation that I would call, “Land Stewardship Rights”. I’m working on developing this concept a bit further and will hopefully be able to share in an article soon.

Worth noting here the approach of Landbanking Group which aims to create an asset class, Nature Equity, that as far as I understand facilitates linking land value with ecosystem service and biodiversity outcomes. I strongly recommend reading their Nature Equity Paper which discusses their approach and concept in much more detail and discern for yourself how it works.

What I’d be curious to see is whether we could develop a structure for an asset vehicle that essentially sits on top of the land itself. An vehicle that can create and hold value associated with the environmental outcomes themselves but does not have to be tied directly to land rights/ownership. I see this as a potential avenue to keep land rights with the land stewards or ensure financial benefit to land stewards in instances where they don’t have land rights but may have land stewardship rights while creating an asset that investors and corporates can invest in and count as an asset on their balance sheet. Not sure if this is viable, but some food for thought.

Is Durability as a construct needed for biodiversity credits?

The recent issue paper defining a biodiversity credit from the Biodiversity Credit Alliance, highlights that one key component of a biodiversity credit is durability.

“Durability means the ability of a project to ensure that biodiversity outcomes on which credits are based are likely to endure for an extended period.”

In my mind, durability is already accounted for in the original definition of a credits as long as a credit is defined as an outcome for an area over a specific time period. This is where biodiversity credits differ from carbon credits. Climate mitigation outcomes only have value at the single point in time of removal or avoided emission, whereas biodiversity outcomes have continuous value for as long as that ecosystem is intact. Therefore, if we were treating biodiversity credits the same as carbon credits in terms of durability (and we don’t have that credit associated with a particular period of time), then we would essentially be saying that whatever entity purchases that biodiversity credit “owns” or can claim all biodiversity outcomes from that area indefinitely.

I could see a subscription model where a biodiversity credit is defined as a specific outcome over a specific area and then the subscription ensures the buyer is paying for the continual value provided by that biodiversity. But if we don’t use a subscription style model, then my thinking is that each credit should be associated with a particular time period and there is no such thing as durability for a biodiversity credit because the entity that purchase the credit for that time period has already received the outcome/benefits.

Now I recognize that we don’t want to create a misincentive where someone can sell a nature credit that has X impact is not incentivized to maintain the delivery of that outcome as time goes on (the main purpose of durability), but also recognizing that we need to continue to compensate and ensure flows of capital to ensure that outcome can stay intact (or continue to regenerate in the uplift context). I think I’d rather have a subscription type mechanism where the payments are, for example, quarterly, than a system where a one-off credit purchase is supposed to sustain a project financially for say 100 years (or longer). Ultimately, the purpose of all of these efforts in creating payment for ecosystem services and biodiversity mechanisms is to incorporate the value of those services into our economic system and ultimately into land-use decision-making. The continual payment approach whether a subscription or a continual purchase of credits that are each associated with a specific time period, I believe, accomplish this goal best.

Subscription benefits

De-risking investment - A long-term subscription commitment would function like a long-term offtake reducing the demand/price risk associated with investments leading to access to more affordable capital (investment) for projects.

Unlocking debt - A long-term subscription likely more attractive to debt providers for project finance than a standard credit/commodity structure and debt is much lower cost of capital to a project proponent than equity.

Lower transaction costs - Subscription structures compared to commodity/credits would likely require a fewer number of transactions and less intermediaries like brokerage services leading to more revenue going to the ground instead of intermediate actors.

Reducing secondary markets - I am not a financial engineering expert, but I think a subscription model would likely significantly limit the emergence of secondary markets around nature credits. Overall, my sense is that this a good thing to keep the money going directly to projects while minimizing the ability for creating ways to make money that might not contribute to the end goal. I have heard and recognize the argument that secondary markets allow investors to hedge their risk, and welcome those with more experience with secondary markets to influence my thinking here.

Financial planning - I’ll put this one as a soft positive as it would be interesting to get a corporate to weigh in on directly. My sense is that a subscription will be easier for corporates/governments who are offtakers/subscribers to do long-term financial planning as they know exactly what their financial commitment is, recognizing, that like any subscription (ie Netflix upping their subscription price last year) the subscription is likely to change in price over time due to a myriad of conditions.

Subscription limitations

Long-term commitment complications - A standard subscription model allows you to cancel your subscription at any point. This inherently does not foster longer-term commitments to particular regions. Therefore, we may want this to look more like an offtake rather than a subscription, or at least a multi-year or even multi-decadal subscription where corporates commit to longer-term temporal (monthly?) payments for nature positive outcomes from a specific region.

But, the project proponents might want to retain the ability to change their prices or do shorter-term subscriptions to be able to try to get higher prices for their production. This is where I think we have some hard decisions to make as an overall industry of whether we want this to function more like a true market or a quasi-market mechanism. The benefit of more of a market approach in my mind is higher risk, higher upside for project proponents. For example, not locking in long-term subscription prices allows for greater ability to charge more if dynamics change, but also means that the project could be left in the lurch if market dynamics shift. If we take more of a quasi market approach and do longer-term subscription of offtake type commitments, that reduces the risk to the project and encourages longer-term commitment and investment in a particular region.

Does it put nature on the balance sheet? - It is likely that a subscription approach will fall in the liabilities side of the balance sheet rather than an asset. Treating nature as an asset instead of the subscription approach could lead to more willingness by corporates to take action if they can count investment into nature as an asset (beyond reducing their nature-related financial risks). Of course, if we are talking about land, then we need to consider who ultimately owns that asset (land). One interesting question is how to design a mechanism where corporates could invest into nature and count it as an asset on their books without owning the underlying asset itself. We want to make investing in nature a positive financial decision for corporates but without such initiatives leading to further land grabs.

Or maybe it’s corporates that pay for the outcomes for which they are beneficiaries (through a subscription for example) and that is combined with an asset approach as well where investors are investing into nature as an asset where returns come from corporate (or government) payment for outcomes with land rights or land stewardship rights staying with the traditional land stewards.

Ex-ante vs Ex-post - What happens if the project doesn’t deliver an expected outcome one month? Or do we take a weighted average? And a subscription isn’t necessarily a payment for outcomes, so the subscription may be conditional such that if the project doesn’t deliver outcomes for a certain period of time, then the subscription can be cancelled. Conditions around continuity of delivery is definitely one still to be worked out under a subscription or long-term offtake model with credits that are associated with a specific time period.

Reduced Degradation vs Uplift vs Stewardship - Most nature crediting mechanisms have highlighted three types of projects. A project that reduces degradation (Reduced Degradation), a project that actively restores degraded lands (Uplift) and a project that keeps intact ecosystems intake (Stewardship). A subscription model could potentially start with a reduced degradation project that then transitions into uplift and then into stewardship, or anyway along that pathway. One question is whether the credit value and the claims that could be made with that credit could/should be different depending on the stage of the project. This isn’t necessarily a red flag for a subscription model, just flagging as an area that needs more thought.

Parting Thoughts

After all the reflections above, I think where I’m starting to land is that whether we want to call it a credit, or a subscription, the key to making a mechanism for paying for nature positive outcomes work will be long-term offtake commitments by buyers (whether private or public sector) to pay for the outcomes from a project.

Whether it’s committing to buy a 10-year/20-year/50-year/Indefinite(?) bundle of credits or setting up a subscription that has a 10-year/20-year/50-year/Indefinite(?) duration, the longer the commitment from buyers, more likely the better outcomes will be for securing finance and ensuring companies and government entities are place-based committed and invested in long-term nature recovery, conservation and sustainable land use.

Thanks for indulging me on these questions and very much welcome your thoughts, opinions, reflections.

- Eric

Excellent Article - This practice of long-term stable biodiversity credit flow, similar to the long-term stable consistent income streams, similar to carbon permeance or renewables (consistent $ per kwh) is being practiced in certain jurisdictions of Australia, with a worthy example of Victoria Australia.

Typically, these these income streams are government-supported, held in custody and slowly disbursed by the government over 10 years. It makes a lot a sense for a private project proponent.

Take a look at this private broker: https://www.vegetationlink.com.au/offsets

The fee paid by the offset buyer is held in trust by Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) or Trust for Nature and paid to the offset site landowner in instalments over 10 years.