Want nature positive? Agriculture is the first beachhead.

But instead of picking sides in the fight, we must unite environmentalists and farmers.

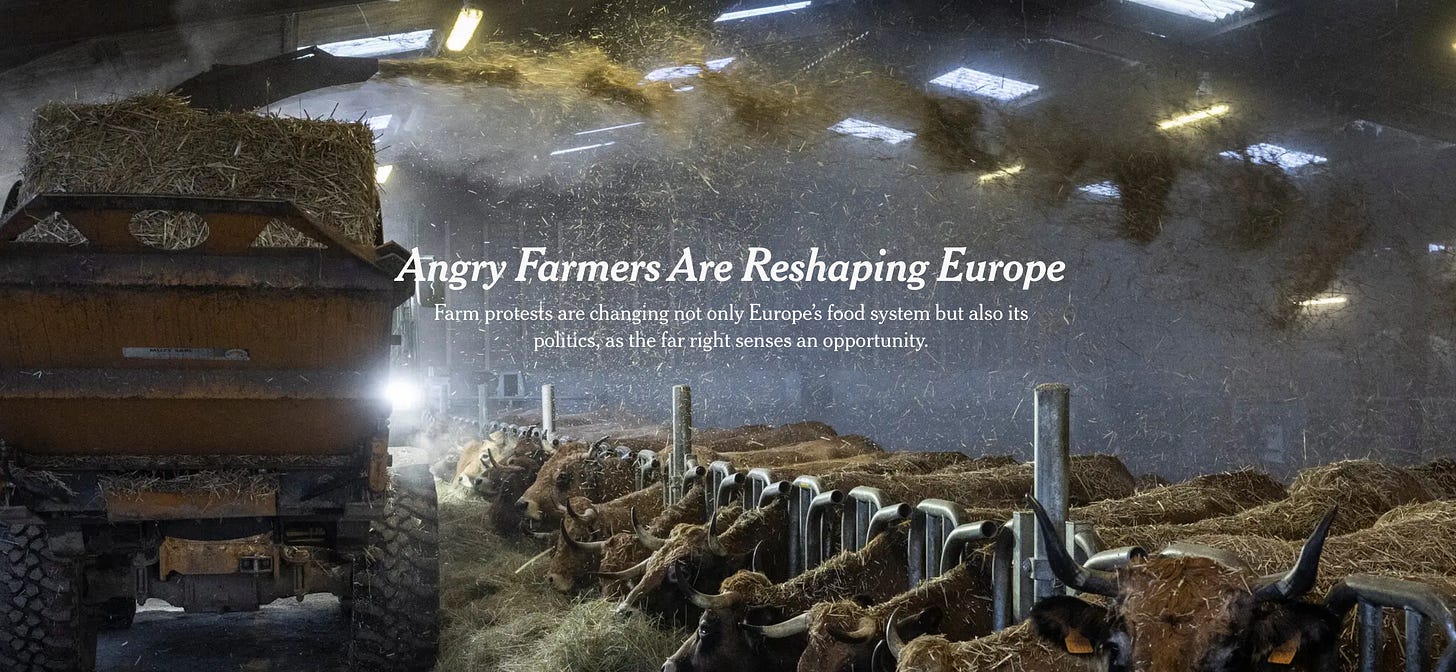

Thanks to Dan Firger for sharing a New York Times article published last week, Angry Farmers are Reshaping Europe. It details the how EU regulations on how farmers in Europe produce food have led to mass protests and may also be influencing a political shift in Europe towards less regulation and was the inspiration for this reflection on agriculture, farmers, environmentalists and the nature positive movement.

I don’t have much experience with farming, but I can certainly empathize with private/smaller scale farmers highlighted in the article. Non-corporate farmers are struggling to make ends meet financially and the EU proposing new regulations which further increase the cost of doing business or reduce yields is not helping.

“Between 2005 and 2020, the number of farms in the EU decreased by almost 40%, forcing approximately 5.3 million farmers out of business.” (source)

On the other hand, I agree with the intention of these regulations, to ensure the provision of ecosystem services and biodiversity that are fundamentally necessary to have a stable climate and local ecology that not only is good for nature, but will enable us to continue to produce food over the long-term.

We need to produce food today. And we need to make sure we’ll be able to produce food in 10, 20, 50, 100 years.

The issue is that currently, non-corporate farmers largely have to choose between the two options, either:

Grow food for today while compromising the environmental conditions necessary to produce food in 10 years.

ORTry to shift practices to ensure environmental conditions to produce food in 10 years but not be able to continue to run the business today.

And it’s important to note, that it’s not only the “Trumpian” farmers of Europe that are frustrated. Take an example from the NYT article of a couple that graduated with engineering degrees but decided to come back to the land to run an organic farm.

Over the past five years, they built a 700-acre organic farm in eastern France where they grow wheat, rye, lentils, flax, sunflowers and other crops, as well as raising cattle. They went into debt as they bought and rented land.

If their path is to lead to the future of farming, it must be made easier, they said.

Mr. Merlo, 35, sees a “crisis of civilization” in the countryside, where automation means fewer workers, the work is too arduous to attract most young people, and credit for investment is hard to obtain. He joined one protest out of extreme frustration. “We don’t count the hours we work, and that work is not respected at its just value,” he said.

“New norms for a greener planet are necessary,” Ms. Cruz Mermy, 36, said, “but so are fair prices and competition.”

So what’s behind all this?

One issue (that I won’t focus on today) is related to European farmers not able to compete with the prices of goods produced overseas.

The other issue, that is more pertinent to my area of focus and likely all of you who read these articles → We want farmers to transition to regenerative, or at least more sustainable agriculture, but yet we are not compensating rewarding them for good practices nor are we providing them with the financial resources/mechanisms to support a transition.

Problem #1 - We don’t value and pay farmers for the good that they are (or could do) with respect to producing food more in balance with ecosystem service provision.

We just say what they cannot do but don’t provide them with the means or compensation for alternative approaches. We must start with valuing and compensating farmers for ensuring ecosystem service provision (including climate mitigation). It’s great that the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures, the Science-based Targets for Nature and GRI’s Principles for Banking Nature-related Guidance are starting to push us to measure and value nature, but until we are actually paying farmers for these positive outcomes, like we are starting to do for carbon sequestration, the business model simply will not work for them to change their practices.

A 2021 EU Parliament Report, Carbon Farming - Making Agriculture Fit for 2030, highlights:

“Close links between carbon farming and biodiversity mean that carbon farming can help deliver biodiversity policy objectives, and vice versa. 40% of the Natura 2000 area is farmland, offering potential for the Nature Directives to be used to implement biodiversity-friendly carbon farming actions. Where carbon farming leads to restoration of degraded habitats, it can deliver win-win benefits for climate as well as the EU Biodiversity Strategy and forthcoming EU Nature Restoration Plan. To ensure win-wins, carbon farming must monitor biodiversity impacts, consider local context, and exclude mitigation measures that are harmful to biodiversity.”

But what this and many reports I have read are failing to capture, is what are the mechanisms for compensating farmers for these carbon and biodiversity outcomes? Not to mention, maintaining soil fertility, reducing erosion, increasing water retention, the list goes on. The payment mechanism (offtake) must come first, whether from the public or private sector, then we can start to address the other elephant in the room which is how we fund/finance the transition that leads to the outcomes that farmers (or the investors) will get paid for.

I believe that most farmers understand that the actions they are taking today are not sustainable for the long-term and want to make that transition. This is what makes them such a valuable ally to the environmental movement, not an enemy! Whether that compensation comes from corporates via value chain work or governments, we must get money to farmers asap rewarding positive nature outcomes to bring farmers and environmentalists under the same banner.

Where are regulations (the stick) likely the right fit? Major corporations can and should be regulated because they have the financial buffer to make changes and still turn a profit. Smaller scale farmers in Europe (and smallholder farmers around the world) should not be regulated, they should be incentivized. Knowing when to apply the stick and when to create the carrot is imperative to achieving the nature positive transition.

Problem #2 - Any transition to regenerative or more sustainable agricultural practices takes time and means a reduction in yields and therefore income for a period.

And this doesn’t only apply in Europe, across the Global South, there are many organizations such as One Acre Fund that are working to help smallholder farmers make the transition to regenerative agriculture. I’ve had many enlightening conversations over the past few months with John Mundy, Director of Global Partnerships, who has built models for this transition in countries across the Global South and the learnings are that it’s usually 5-7 years for farmers to be able to become profitable again after adopting regenerative practices.

Whether in Europe, SE Asia, Africa, Latin America or anywhere, ensuring farmers receive the finances/subsidies to survive this “valley of death” in regenerative farming is absolutely critical to ensure they can produce food today and contribute to a functioning ecological system that will ensure they can produce food for generations to come.

One interesting design flaw in the EU subsidies for farmers highlighted in a recent Birdlife International article, “farmers are rewarded with subsidies based on the number of hectares they cultivate. The result? About 80% of the EU farming budget goes to roughly 20% of farmers – the biggest and richest.”

According to a 2023 survey by the European Commission, 83% of all farmers in the EU experienced an increase in production costs, but only 12% managed to significantly increase their selling prices. The total financing gap for EU agriculture is now €62 billion ($67 billion). Some of the increase in production cost is due to existing regulations that are driving towards nature positive outcomes, but many new regulations, such as the The Soil Monitoring Law, are yet to take affect but will add more costs to production. The Soil Monitoring Law would require EU member states to monitor the health of their soils and fertilizer use and will in effect give soil similar protections received by air and water and enable the capture of more CO2.

During my research, I came across many niche private funds, like HeavyFinance, that are being stood up to help finance this regenerative agriculture transition. But a €50 million fund is a drop in the bucket compared to what is needed and it appears that the return desires of private finance just won’t work for many farmers, concessional capital and government funding needs to come first.

In the global south, this need for concessional capital and government funding is even more of a need. And most Global South countries do not have the financial resources themselves to do it, so we either need developed country governments to help finance the transition with little expectation of a return and any private companies that have supply chains that overlap with smallholders to make direct investments into that transition, hopefully driven by TNFD and SBTN and other policy initiatives aiming to drive nature positive action and outcomes in corporate supply chains.

One last note, as we continue to develop and structure all of these mechanisms and policies and financial tools, let’s also invest in the deeper work. To get back in touch with the interconnected and interdependent reality ecological and human systems and inspire a world where everyone is intrinsically motivated to act in pursuit of a sustainable equilibrium between humans and nature.

Great article Eric! Thanks for sharing. I appreciate the distinction between stick and carrot and WHO each of these methods are appropriate for. Completely agree that we won't see change fast enough without the unique combination of regulation and compensation.